P.O. Box 80, Cooper Station

New York, NY 10276

212-673-7922

208-693-6152 fax

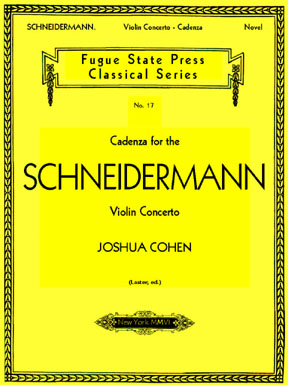

Cadenza for the Schneidermann Violin Concerto

Cadenza for the Schneidermann Violin Concerto is a wild, wide-ranging, freewheeling and ultimately lonely work that speaks to the most crucial aspirations of literary fiction's much-maligned "experimental" genre....What distinguishes Cadenza from postmodern irony is the genuine compassion an observer will feel for Laster, despite his insistance on being both instrument and executor of his own destruction....The impression of his gaze is as unavoidable and inevitable as the tragedy awaiting his cadenza's finale.

The novel begins with Schneidermann's friend--his last friend, his

only friend--the violin virtuoso Laster, onstage at Carnegie Hall. He

has finished playing the first movement of Schneidermann's last

composition, his Violin Concerto. At this point he is supposed to begin

his cadenza...his solo. Instead, he drops his instrument and lifts his

voice, delivering the text of this novel unto the audience, held captive

through night into morning only by dint of the spiel.

In its obsessions, its black humor, and its depth of multiple

cultures, Laster's voice is a final great unwanted gift from the old

world to the new. Somehow, at age 25, Cohen has created a requiem for

high culture that in its disgusted wisdom, its layers of historical and

cultural references, would seem to have come from a man of 90--except

for the ruthless and hilarious energy of its gaze.

Joshua Cohen, born in 1980 in Southern New Jersey, is a novelist and

writer of short stories. He is the author of one previous book of

fiction: The Quorum (short fiction, 2005, Twisted Spoon Press).

Having lived for four years in Prague, and worked as a journalist

throughout Eastern Europe, Cohen now lives in New York City. His essays

appear regularly in The Forward. His fiction is often engaged

with Jewish culture, and questions received ideas concerning identity

both national and religious.

the author writes:

"I was born into a generation way after any idea of the death of the

novel. And yet that death, or that that death hasn't yet happened, still

fascinates me. I wanted to write about death: our own human

ashes-to-ashes mortality, yes, but also about the death of an art. And

music was the most attractive to me. Why? It was strange. Pen to paper

with music in the head is a method that to me seems to come from another

universe, to be informed by processes certainly foreign to most. Words

on paper can be called a book, globs on canvas can be called painting,

but music requires practitioners. Second-parties to whom we are never

invited. In our age, these people have changed, have become something

different. Exclusive. Elite. Music itself--as tonality exited

stage-right--declared itself dead, suicided actually, just one quaver

one breath one stroke of the bow short of irrelevance, following the

atomizing of the Second World War. Jews died too. I say in the novel, or

I have Schneidermann say, that music is the Jew of art, that the Jew is

the music of humanity. That neither have reasons, practical

justifications, in-the-world purpose. That the qualities of both are

intangible, unprovable, evanescent. But far from making huge noise about

art, music, the Jew and Judaism--after all, what I have Schneidermann

say is Schneidermann's problem--my novel is about a man as a man, as a

practitioner of music and Judaism, as an artist. And it is about his

death. The sound--because for me writing is as much about sound as about

idea--is one of void. Of nihility. No-one's-listening... (what's the

word auf Deutsch?) In the end, this novel is about the death of a

way-of-hearing. Endless, it's about the death of an ear."

by Joshua

Cohen

$18.00 390 pp ISBN

978-1-879193-16-1

--Miles Newbold Clark, The Literary Review

It's no accident that Joshua Cohen's debut novel, Cadenza for the Schneidermann Violin Concerto, comes packaged in a guise of sheet music so exact that it will cause musicians to do double-takes, wondering why they've never heard of this Schneidermann fellow. Cohen himself delivers the performance within, a sprawling 380-page verbal onslaught, all of which purports to be occurring on-stage at Carnegie Hall over a single night. Readers...will find themselves amply rewarded--dazzled by Cohen's language, his knowledge of music and history, and most of all the sheer chutzpah of his prose.

In lieu of an unbroken dream, what we get is akin to the restless, late-night perambulations of an insomniac sifting through his life, the back-and-forth motion of text across the page recalling a violinist's bowing...The character of Schneidermann is inherently fascinating, worthy of this epic treatment: steeped in the knowledge of music and philosophy, he...holds forth on history, music, philosophy, theology, art, Jewishness, and the Holocaust. The book consists largely of a sustained, erudite set of free-associations on, for instance, the difficulty of writing about music, what it means to be Jewish, what makes some art transcendent versus mediocre, and the role of the individual in directing the arrow of history....Cohen baldly exposes warts, rendering characters who are sympathetic yet flawed. Both main characters have a tragic dimension, but it is Laster who ultimately cuts the most tragic figure: six-times over a failure as a husband, estranged from each of his children, and left in the end without even his erstwhile companion.

Cohen's book sometimes reminds one of Beckett's trilogy in its comic sensibility, its embracing of the lowly and bodily, and the implication that speaking is fundamentally a way of holding the abyss at bay. What sets Cohen's book apart from such forbears is how wonderfully, deliriously steeped it is in the world of music. The book teems with musical allusions and puns, with its descriptions of "flat daughters [and] a sharp mother," its reflections on Beethoven's "mania for motivic expansion," and even a device as simple as replacing "shhhhh" with "pppppppppp." It's not all puns, though. Cohen's own writing is best characterized as musical...grappling with its weighty themes in language that soars with a virtuoso's touch and intensity.

--Tim Horvath, Barnstorm

Joshua Cohen has, at first glance, both challenged himself to the astonishingly difficult task of entirely narrator-driven storytelling and formatted his nostalgic novel to be innovative and forcibly paced to the internal metronome of its narrator. This novel, the first by Cohen, opens in a seeming cirque de cérébrale address of a Carnegie Hall audience by a virtuoso violinist, Laster, having just played the final composition of his friend, composer Schneidermann. This near-manic oration delivers a portrait of Schneidermann's music, frustrations, and nature, while, initially, Laster offers very little information about himself....

Perhaps it is Cohen's excellent command of vocabulary, which becomes impressive, as the dialogue continues, that such frenetic storytelling can take place without any repetition of words, even thoughts. Cohen doesn�t care much about structural, grammatical, or usage rules, but only because he clearly knows them all well enough to break, bend, and reconstruct them on his own terms.

Slowly, tiny threads of the Holocaust and whispers of mid-20th century American anti-Semitism slip in and slide between words and suddenly, quite suddenly, in fact, the notion arises that if poor Laster should stop talking, should slow his anxious speaking pace for even a moment, his memories might prove too painful, his burden too much, and all of his thoughts would become too jumbled for him to even process. Somehow, Cohen makes the reader feel a sense of responsibility toward his characters. It becomes so glaringly obvious that a beautifully tragic story has sprung up and unfolded and you are engrossed and cannot bear to let Laster suffer. Without realizing a metamorphosis at all, the readers suddenly find themselves responsible for this pained and animated narrator.

Cohen...delivers such a heartbreaking story which speaks to both European-American Jewishness and to broader themes of creative frustration, nostalgia, and quietly contained grief.

--Amy Güth, Bookslut

So he, Cohen, writing with amazing energy but less like the

twentysomething he is than a crotchety octogenarian on a month-long

meth binge, has him, Laster, the virtuoso violinist, protégé,

financial supporter, and "performing monkey" for him, Schneidermann,

the brilliant but obscure composer, supposed to perform the cadenza,

launch instead into a 300-page verbal improvisational fusillade

without so much as a single inhalation or rest beat (15 hours! So

maybe I should read his short story collection, The Quorum, instead!),

not so much a story as "talking, eulogizing, ranting, sermonizing"

about his, Laster's, but more so his, Schneidermann's, life but more

so a cultural/political/musical/religious/historical consideration of

the entire 20th century and the end of classical culture from a

Hungarian/German/Jewish/New York perspective. He, Cohen, will drive

most readers away screaming "Oy! Too much is enough!" but they, the

readers who stick around, will be delighted, if exhausted, which is

why you, most public and academic librarians, should buy this,

Cohen's, book, which might just become a cult classic.

--Jim Dwyer, Library Journal

This brilliant first novel is a portrait of an artist at the end

of an art form. The elderly Jewish-Hungarian composer Schneidermann, who

survived a musical education, survived the war, survived Europe,

survived the neglect of all his music, finally and suddenly vanishes

during a movie matinee on the Upper West Side of New York.

about the author:

--Joshua

Cohen